![Utsuro Bune Print]()

Translated and Adapted from Toen Shōsetsu, Hyōryū kishū, Ume no Chiri, Japanese Wikipedia, and Other Sources

Legend or fact? In the early 1800s, a strange iron ship with crystal windows drifted ashore off the coasts of the Hitachi province, modern day Ibaraki prefecture, where it was found by locals. By most accounts, inside was a mysterious woman with pale, pink skin and white-frosted red hair. She spoke an unknown language and clutched a square box made of some pale material, which she would not release. Unsure of what to do, the locals packed her back in her ship and pushed her back to sea.

It would seem to be a fairy tale, but the same woman and the same mysterious ship has been recorded drifting to shore in different locations, and the various accounts match each other almost exactly. Ufologists have co-opted the story claiming it is evidence of an early UFO siting, although this is extremely dubious. After all, the “F” in UFO stands for “Flying,” and that is something the Utsuro Bune definitely did not do. It is strictly a boat. Other’s claim it is some form of early submarine, or an attempt at a new technology for ocean-going vessels. Whatever the Utsuro Bune was, it remains a unique entry in Japan’s weird history.

What Does Utsuro Bune Mean?

In defining Utsuro Bune, the “bune” part is easy. 舟 (bune) means “boat,” plain and simple. “Utsuro” presents more of a challenge. When written, the hiraganaうつろ (utsuro) is used almost exclusively, giving no clue as to the exact definition. There are a few different meanings that could be attached. The most common translation is “empty” or “hollow.” Another reading is “quiver” like a quiver for arrows.

Another, obscure usage of utsuro describes the hollowed-out tree trunk of a sacred tree. There is some speculation that “utsuro bune” originally described a hollowed-out tree trunk into which a sacrificial victim was stuffed and then put out to sea; although there is very little evidence for this other than the name.

The Legend of the Utsuro Bune

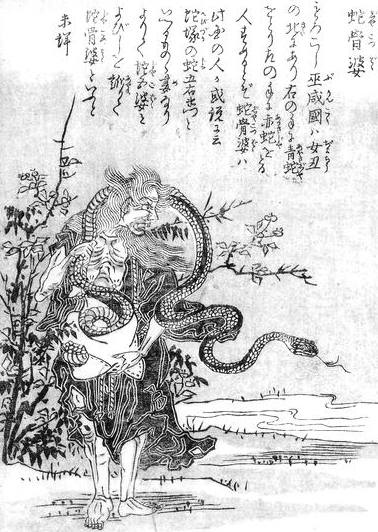

The oldest account of the Utsuro Bune comes from a book thought to have been published in 1815, called Oushuku Zakki (鶯宿雑記; Miscellaneous Notes from the Nightingale Inn). The one-sheet text and illustration gives a short description of the event, and lays down the basic facts.

![Oshuku Zakki Utsuro Bune]()

The most well-known account—and the most detailed—comes from Kyokutei Bakin and his book Toen Shōsetsu (兎園小説; Stories from the Rabbit Garden). Kyokutei lived in the late Edo period. He was what was called a bunkajin, meaning an intellectual, a cultured man of letters. Kyokutei was brimming with curiosity, and like many in the Edo period had a passion for the supernatural and the weird. He hosted a monthly gather of knowledge-seekers such as himself, called the Toenkai, Meeting of the Rabbit Garden. Kyokutei and his fellow bunkajin would gather to swap tales and share interesting or weird stories they had heard—something like what we would call a Writer’s Circle in the modern parlance.

The Rabbit Gardern knew all of the best weird tales of the day. They swapped first-hand accounts of yōkai and yūrei and urban legends, anything with the ting of the occult. The Utsuro Bune was a type of tale was called a michi tono sogu (未知との遭遇, eye-witness account). They chose the best of these stories and Kyokutei edited them and compiled them into the Toen Shōsetsu collection. Several of Japan’s famous weird tales come from that edition.

Kyokutei’s account of the Urotsu Bune is unusual for being so specific, even though it was written 22 years after the incident occurred. It is highly possible—and even probably—that one of Kyokutei’s “rabbits” read the account of the Miscellaneous Notes from the Nightingale Inn and decided to fill in the details.

——————————————————

Urotsu Bune no Banjo – The Foreign Woman in the Hollow Boat

Translated from Toen Shōsetsu

![Utsuro Bune Tales from the Rabbit Garden]()

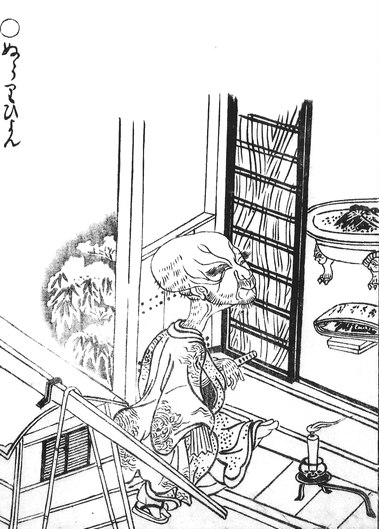

On the 22nd of February, in the 3rd year of Kyowa (1803), in the Year of the Ox, a strange object that looked like a small boat was spotted off the shore of Tsuruhama. The fisherfolk who lived in that area observed the strange vessel and took to their boats and rowed out to meet it. With great effort, they towed the mysterious objects into the shallows and drug it onto the beach. It was unlike any boat they had ever seen.

The vessel measured about 3.30 meters tall and 5.45 meters wide. It was round as a ball, and resembled a covered incense burner. The top half was made of what looked like red-lacquered rosewood, with windows patterned like folding screens—only with glass panels instead of paper. The whole thing was sealed watertight; with the seams plugged with something like pine pitch. The bottom of the vessel was bound with ribs of metal—possibly bronze or iron. It is speculated that the metal plating protected the boat from impact with sea rocks. Everyone was much amazed when the top swung open, as if hinged by some hidden latch or mechanism. Then the woman appeared.

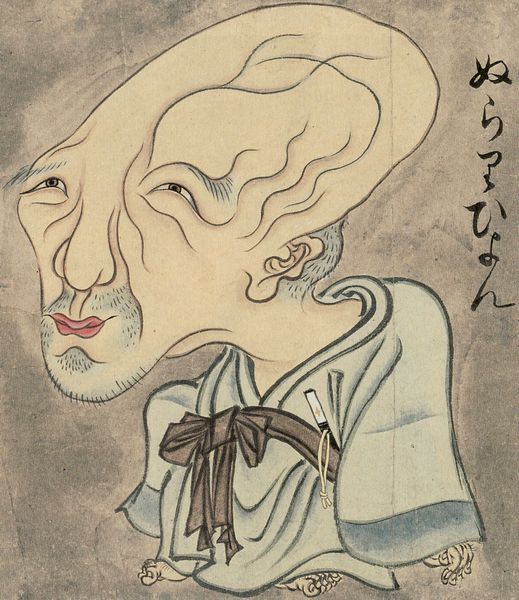

Her face was a pale pink color, and her hair and eyebrows were vivid red. Here hair hung down her back, and had been lengthened with strips of something white, either animal fur or a kind of fabric. The extensions had been covered in white powder, almost like flour. What it was exactly, we have no way of knowing. Her dress was elegant and of strange material, tight at the top and loose at the bottom. The village women were very interested in seeing how she had achieved the effect of her hair and dress, but it remained a mystery.

When the villagers attempted communication with the woman, she responded in an unknown language. She was about 1.5 meters tall, and carried a square box. This box appeared very important to her, and she would not release her grip on it for an instant. She would not let anyone even get close to it.

The villagers checked the interior of the mysterious ship, and found two sheets, and two small containers of water (the water supply was insufficient for survival, so the ship must have had some means of generating fresh water). There was some form of baked goods and some kind of meat twisted together like a rope that served as provisions.

The villagers had a discussion about what to do with the strange woman and her boat. An elder of the village proposed the idea that perhaps she was a princess of some distant country. Perhaps the princess had been married, but took a commoner as a lover. As punishment, her father the King had her lover’s head chopped off and put into a box, then the princess was placed in this odd vessel and abandoned at sea. After all, he reasoned, you couldn’t directly execute a beloved royal princess. This way her life was in the hands of the gods.

The elder said that would explain her devout attachment to the box, and her resistance to relinquishing it or letting anyone look inside. The elder said he had heard of things happing like that before, and he remembered some story of a woman washing ashore in similar circumstances long ago.

It was decided that the best thing to do would be to put the girl back into her hollow boat and return her to the sea. It seemed cruel, but the villagers did not want to interfere with the intentions of some foreign state. So they put the girl back in and rowed her back out into the deep sea and set her adrift again, leaving her to her fate.

It was also noted that the inside of the hollow boat was covered in strange writing. Some suggested that perhaps it was the writing of Great Britain, or perhaps the girl was some lost princess from the distant country of America. But there was no way to know for sure.

——————————————————

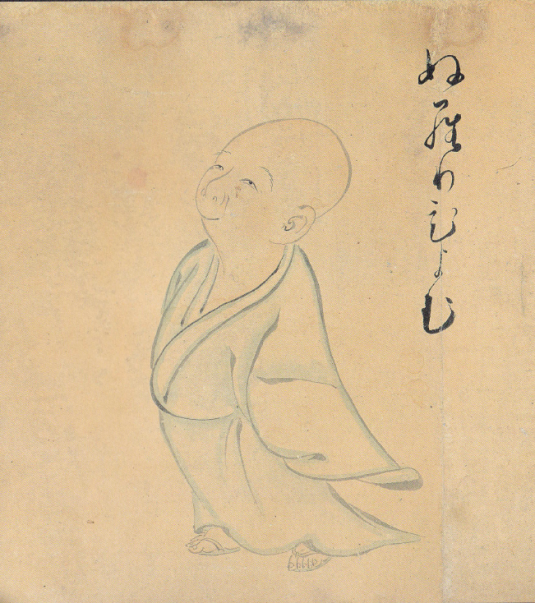

Other accounts of the Usturo Bune soon surfaced, each with a slight variation. If you believe all the accounts, the poor girl kept drifting ashore to various spots in Japan, each time only to mercilessly returned to the ocean. It seems no one was willing offer her a helping hand.

——————————————————

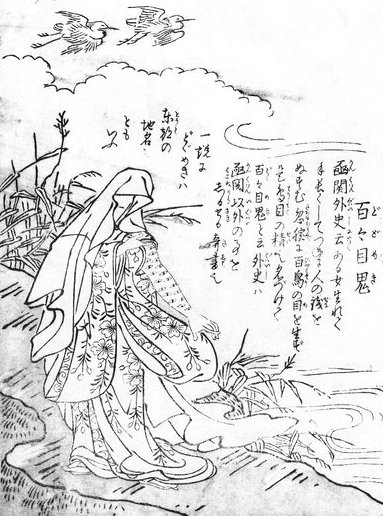

Translated from Hyōryū kishū (1835: 漂流紀集: Diary and Stories of the Castaways)

![Utsuro_Bune_Castaways]()

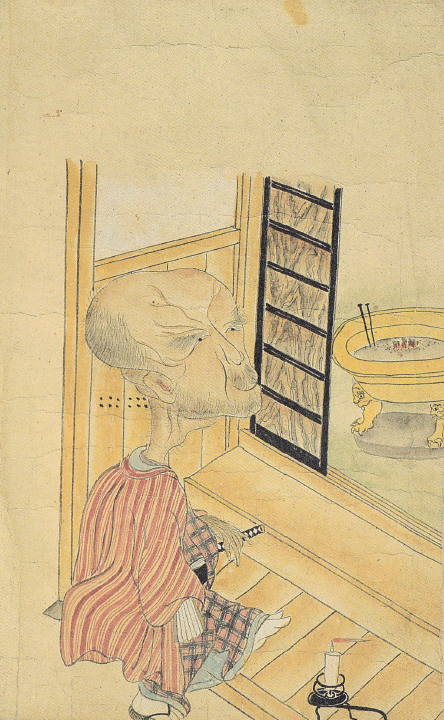

Hitachi province, Shakehama. An odd boat looking the same as this illustration drifted ashore. Inside was a woman between the ages of 18-20, with a pale complexion, red eyebrows, and hair that matched the red color of her eyebrows. Here teeth were white, and her lips a deep crimson. Here arms were slender, and she could be considered beautiful. She was well-mannered and calm. As you see in the picture, she was carrying a wooden box that seemed to be very important to her. We do not know the contents as she would allow no one to handle the box. She spoke, but not in a language that could be understood by any of those present. We assume she is a foreigner, not only by her strange speech but because her features and coloring are not those of a Japanese or other Asian person. Inside her strange vessel she has some provisions, what looks like baked goods and some meat that has been treated in some manner. But the exact contents are unknown to us. She has a large tea cup. The construction of her ship was also unknown, made of equal parts metal, wood, and some form of ceramics. Inside we could clearly see the writing that is reproduced on this picture.

Description of the Boat: It was about 3.3 meters tall, and 5.4 meters wide. The body appeared to be lacquered rosewood bound with iron or bronze. There were windows made of crystal or glass. The woman appeared to be about 18-20 years old. She had a pale complexion, with red hair. There was writing on the left side of the ship, reproduced faithfully.

——————————————————

Urotsu Bune no Banjo – The Foreign Woman in the Hollow Boat

Translated from Ume no Chiri – (1844; 梅の塵 : The Dust of Plums)

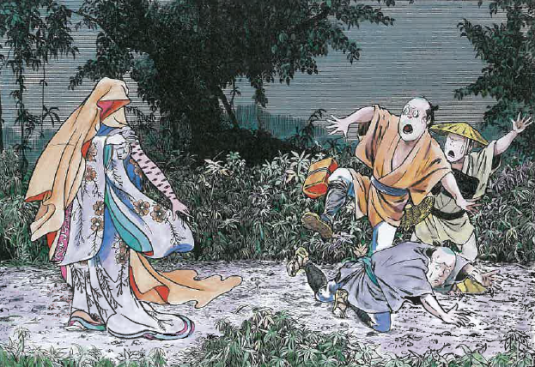

![Utsuro Bune Color]()

This happened in the spring of the 3rd year of Kyowa (1803), in the vicinity of Haratonohama. A strange vessel drifted ashore.

This vessel was shaped like a hollow sphere, looking something like an iron cooking pot. Around the circumference it was edged like the lip of a pot. The top half of the sphere had the appearance of black lacquer, and was covered in windows. The windows looked like shoji paper screens, and were covered in some sort of pitch. The bottom half of the sphere was bound with iron ribs, as protection from rocks. It looked like the high-quality iron that comes from the Western countries. It was 3.60 meters tall and 5.40 meters wide.

Inside the strange vessel was a lone woman, who appeared to be about 20 years old. She stood roughly 1.50 meters tall. Here skin was as white as snow, and her long black hair hung down her back like a plume. The beauty of her face was enough to render us all speechless. Her clothes were like nothing we had ever seen before, made of some remarkable and mysterious fabric.

She spoke no language that we could understand.

She carried a small box, the contents of which are unknown. Under no circumstances would she allow others to hold the box or even get near it.

Inside the boat, there were two sheets laid down as some sort of carpeting. They were softer than anything we had ever felt before. For food, she had some sort of baked goods, and some kind of meat. We saw a single drinking bowl like a large tea cup. Everything was patterned with some sort of design, but we could not determine its meaning.

——————————————————

Truth Behind the Legend?

![うつろ舟/江戸時代のUFO?]()

Who knows. This is one of those fanciful bits of history where the real story will probably never be known. It is VERY different from other weird tales of the Edo period, by virtue of being so specific in detail and lacking any supernatural element.

The Utsuro Bune is a classic case of “the legend has grown in the telling.” Modern legend trippers have taken up the story, added their own details, and twisted the story like a modern game of telephone. Modern Japan has embraced the legend—and commercialized it like their own Roswell—creating a recreation/play space of the Utsuro Bune at one of the locations where it apparently touched shore.

![Utsuro_Bune_Park]()

But at the core is always Kyokutei’s original account of a strange woman in a strange boat. And that mystery is good enough without embellishment!

Translator’s Note:

I discovered the Utsuro Bune completely by accident, and then became hooked on it. A little too much, I think, because I started researching and translating Utsuro Bune legends when I should have been working on other things!

There is SO much written on the Utsuro Bune that I could barely cover it here. Separating out all the different elements can be difficult. If you are interested in reading more, the English Wikipedia article is very extensive and has lots of good links and resources. In fact, the Wikipedia article is so good I almost didn’t bother to do this entry. But I noticed the one thing that was missing was translations of some of the original Utsuro Bune stories! So I tracked down a few of them and translated them!

![]()

.) In the 1960s Mizuki helped pioneer the concept of gekiga or art manga, in the magazine Garo, transitioning comic books from children to adult readers.

.) In the 1960s Mizuki helped pioneer the concept of gekiga or art manga, in the magazine Garo, transitioning comic books from children to adult readers.

and the epic

and the epic  . He continues to fight against right-wing militarism and government mind control, in favor of what Thomas Jefferson called The Pursuit of Happiness. Like himself, he prefers a world “bursting with dreams.”

. He continues to fight against right-wing militarism and government mind control, in favor of what Thomas Jefferson called The Pursuit of Happiness. Like himself, he prefers a world “bursting with dreams.”

is coming out in a couple of months. I have been working to make the final edits and get the book design perfect, as well as attending various conventions in support of the launch. If you haven’t already pre-ordered it, PLEASE do so! I need as many preorders as I can get to show booksellers that there is an audience for this kind of work.

is coming out in a couple of months. I have been working to make the final edits and get the book design perfect, as well as attending various conventions in support of the launch. If you haven’t already pre-ordered it, PLEASE do so! I need as many preorders as I can get to show booksellers that there is an audience for this kind of work.